As with nearly every creation, when making an instruction video one should first ask what the purpose of the video is. Is the goal to motivate people, instruct them or simply to demonstrate something? The goal of the instruction video largely determines the different elements and method of the video.

Next one should determine the type of video it will be: animation, realistic or real. Then a distinction should be made between a static, dynamic or interactive video. In a static video, for instance, the film is recorded from a single stationary position. In a dynamic video, the camera position changes locations periodically. In an interactive video, the approach is to have the user become actively involved in the video by stimulating interaction with questions or by asking them to confirm something via, say, an interactive button.

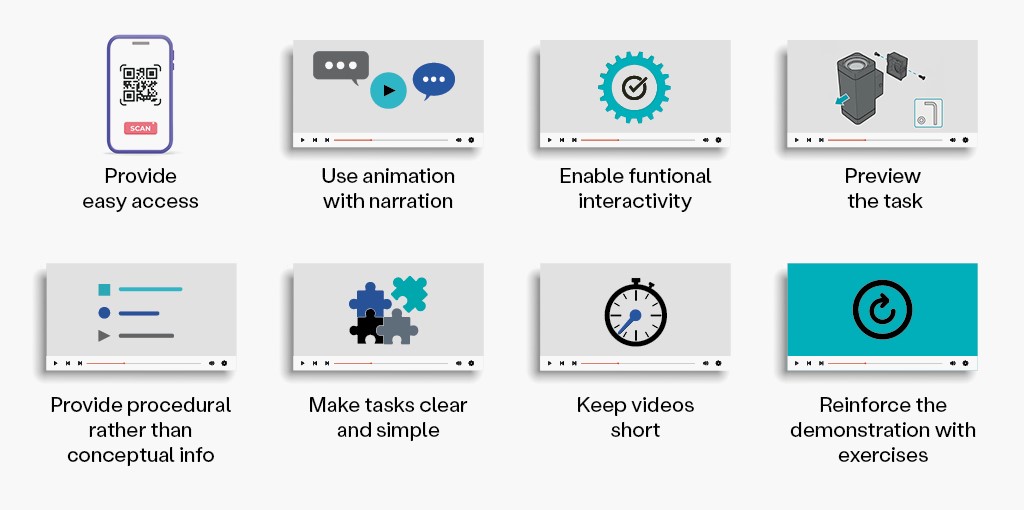

When developing a visual instruction, one should also – according to “Plaisant & Schneiderman” – take the following basic rules into account:

- provide preparatory and/or procedural information

- keep the segments short

- make tasks simple and clear

- encourage a mix of tasks and practice

- use the spoken word

- do justice to the interface

- demonstrate in order to draw attention

- give the user some control

In the study conducted by Hans van der Meij, the learning processes used in simple instruction videos and in interactive instruction videos, respectively, were tested. The study focused on instructions concerning how to perform text layout actions in Microsoft Word. The group of respondents in the study consisted of 55 beginning and 55 advanced Microsoft Word users. They were divided evenly over two study groups. In one target group, the instructions were given via a simple instruction video. In the other group, they were given using an interactive instruction video.

In the interactive instruction video, an interactive table of contents was introduced at the left side of the screen. Using this, the user could choose which actions he or she wanted to perform. A voiceover explained the action as the action was shown on screen using written text. A clear distinction was made between preparatory information, task-oriented information and information on the result. Actions were demonstrated by a moving cursor, which showed exactly what had to happen within Word. The other group of respondents received the same instructions, but then without the benefit of the interactive elements above.

After both groups had followed the instructions, a test was conducted in order to determine whether the users were able to perform the actions independently. The result was that the group of respondents that had received interactive instructions were much more able to repeat the process than the other group were. There was a significant difference between them. This led to the conclusion that interactive videos are much more effective. Upon completion of the test, a number of questions remained:

- Was the video more motivating?

- What is the effect with respect to long-term memory?

- What design guidelines are the most critical? Demonstration, practice or interface?

These questions will perhaps be addressed in a subsequent study.